Unsustainable Projects in Armenia: Case of Amulsar Gold Mining by Lydian International

Lydian International Limited company is a mineral exploration and development corporation registered in an offshore zone namely in Jersey, Channel Islands. The Company is listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange and it owns a mining and a number of exploration assets in Armenia. Amulsar gold deposit is its key asset. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) have bought major shares in Lydian but there are other shareholders too, among these the U.S., Canadian and European investment funds. IFC is a 7.9 percent shareholder and has invested over 13 million USD in multiple stages since 2007. The EBRD in its turn planned to invest up to 8 million USD to purchase shares of the company as part of its capital increase. As its existing shareholder EBRD has monitored project advancements together with an independent environmental and social consultant.

Through its 100 percent owned subsidiary in Armenia – Geoteam CJSC (now Lydian Armenia), Lydian expects to extract annually some 10 million tons of ore containing 7.8 tons of gold from Amulsar gold deposit for the rather short period of eleven years. Amulsar license covers a total of 65 km2. Initially it was planned that around 426 million USD of capital investment will be spent on the project during the first two years of its life. According to Lydian’s calculations, over the life of the mine it will contribute around 488 million USD to the state budget through taxes and royalties. Its total contribution to Armenia’s GDP annually will be around 185 million USD or 1.4% of GDP.

Lydian also plans to create jobs at Amulsar in the years to come. According to them, this project is going to create highly paid jobs with approximately 95% of employees being Armenian nationals and will involve around 1,300 workers for construction during the first two years of the project. During its eleven years of production, it will provide approximately 770 jobs at the mine, processing facilities, laboratory and in administration.

The project is expected to move into the development and construction stage mid 2016 targeting first gold production in early 2018. The Armenian Environmental Impact Assessment was approved by the Ministry of Nature Protection (MNP) in October 2014. The Mining Right for the Amulsar Gold Project was approved by the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources of Armenia in November 2014. However, the project has undergone several changes during the past years since modifications have been made to the project’s Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA). The final version of the ESIA has been completed and disclosed in May 2016 and is available here.

Risks of the project: cyanide and its impact on health and environment

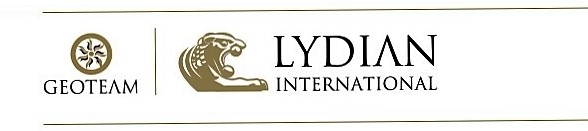

Mountain Amulsar is located some 160 kilometers south of Yerevan – Armenia’s capital, on the border of Syunik and Vayots Dzor regions. It is some 12km away from Jermuk town and 5-7 km away from Gndevaz, Saravan, Saralanj, Kechut, Ughedzor and Gorayk villages. The gold will be extracted from the ore with cyanide. This process is called heap leaching and is considered dangerous. The heap leach facility will be located in Gndevaz village one kilometer away from the residential area. According to legal experts, the permission to construct the cyanide heap leaching facility in such proximity to the residential area is one of the factors in need of legal assessment together with the impact of the method itself on the surrounding environment. According to environmental health experts, both cyanide, as well as the dust caused by blasts in this open-pit mine contain risks for the environment as well as human’s health. They highlight that lead emerges in similar mining activities which affects nervous and blood systems. This increases mortality rate and causes birth defects. Dust containing cyanide in its turn will travel about 30km in radius, accumulate in plants, penetrate the animal chain and human bodies. One of the side-effects of cyanide is negative impact on respiration system.

In 2014 Armenia’s Ministry of Health was questioned about its conclusion on the project. The Ministry said it was not involved in the assessment of the effects caused by the mine. This implies that the positive conclusion of the impact assessment was made without consideration of effects on health and therefore violated Armenia’s Law on EIA, article 5, point 1st. It states that impact assessments should stem from the human right to favorable environmental conditions that ensure health, adequate standards of living, protection of flora and fauna and preservation of ecological balance.

Jermuk resort: impact on water, economic state of locals, insufficient consultations

Additionally, the mining area is considered too close to Jermuk resort and around 6000 residents living nearby (some 12km away). Jermuk is an international resort complex. The pool where sanative waters are located has the status of hydrological reserve and is included in the list of Armenia’s specially protected areas. Investments are thus made here for developing tourism and mineral water spa centers. Article 99 of Armenia’s law on Water declares that in the areas with underground waters activities such as burial, discharge or release of radioactive or toxic waste, blasts that release toxic waste are prohibited. Since open pit mining in Amulsar will be accompanied with blasts as well as heap leaching, experts highlight that in this case a detailed legal as well as economic study should be carried in terms of environmental impact for Jermuk and its waters, as well as in terms of economic gains and losses in long-term perspective. The ESIA of the project has no proper assessment of the correlation between economic gains and losses caused by this project. There is a need to assess the decline of the international reputation of Jermuk resort, possible negative effect of the affected rivers that irrigate nearby vineyards (risking the quality of wine and brandy production), as well as effects on development of tourism and agriculture in long-term perspective.

Although Jermuk has been recognized as a project-affected zone in the most recent (4th) ESIA presented to government in May 2016 (it wasn’t recognized as such in previous ESIAs), it lacks long-term economic assessment for Jermuk. It does highlight Jermuk town as a residency for the future employees of the mine during the facility construction, as well as during the 9-10 years of mining. According to authors, mine employees will thus contribute to the budget of Jermuk town substituting the losses from tourism industry, especially because they will reside there all year round, while the peak touristic season in Jermuk is summer. However, what the ESIA fails to mention is the long-term perspective: mining would tarnish the reputation of Jermuk as a spa resort. Once the mine closes down and the employees leave, the future of the town residents and their economic situation will be uncertain.

This project is thus risky not only for the social-economic situation of the village residents near Amulsar mountain who have opposed the project in numerous hearings. But it also undermines socio-economic state of the residents in Jermuk whose opinion has not been considered due to Jermuk’s exclusion from the impact zone until recently.

Lake Sevan: water reserves of Armenia

Another concern with Amulsar project is its proximity (about 6km away) to one of Armenia’s biggest potable water reservoirs -Spandaryan (with the capacity to hold 257 million cubic meters of water). Kechut reservoir is located some 4.5 km away. Its waters flow to the lake Sevan through Arpa-Sevan tunnel. Streams that feed Vorotan, Arpa and Darb rivers are as well located in the vicinity of mountain Amulsar. Waters of these rivers are used in the area falling under the scope of the EIA as well as in areas outside the EIA zone where they irrigate vineyards used for wine and brandy production. Moreover, Arpa and Vorotan rivers feed lake Sevan which means that Amulsar’s location is within the impact zone of Sevan lake. The project envisages that the heap leach facility will be located within the Arpa River catchment and downstream of Kechut Reservoir. According to Armenia’s law on lake Sevan (article 3), Ketchut and Spandaryan reservoirs, as well as catchment basins of Arpa and Vorotan rivers are part of the catchment basin of Sevan lake. Article 10 of the Law on Sevan declares that activities in the zones directly or indirectly impacting Sevan’s ecosystem in a negative manner are prohibited. Article 108 of the Law on Water in addition declares that in areas of catchment basins it is banned to bury toxic waste that will indirectly affect water resources. This implies that not only the laws on water and laws on Sevan are violated, but in such a case, the residents of the villages near the lake Sevan should also be included in the project as affected by Amulsar project.

Flora, fauna, cultural heritage: matching laws to the mining project

Another concern is related to flora and fauna of the area which will be negatively affected from the project. There are around 248 species of plants, 6 of which are registered in the Red Book of Armenia (i.e. at the verge of extinction). There are also 60 species of mammals, 12 species of reptiles, 2 species of amphibians, 5 species of fish. Environmentalists are concerned with the extinction of these species. Not only there is a potential environmental threat, but additionally laws of the Republic of Armenia (RA) are being twisted in order to fit the Amulsar mining project. One such twist is the decision adopted by the Parliament in 2014 that allows relocation of extinct plant species registered in the Red Book away from mining zone. Legal experts question this decision since it contradicts the RA Code on Subsoil, as well as Laws on Plants.

Article 26 of the Code on Subsoil bans mining in areas where there are graves, natural, historical or cultural monuments as well as habitats of plants and animals registered in the Red Book. Article 17 of the Law on Plants bans any activity in Armenia that decreases the number of flora and fauna species registered in the Red Book or deteriorates their habitats. Both of these laws have higher legal force than government’s decision. However, the mining project is circumventing legal provisions instead of abiding to them.

Article 26 of the Code on Subsoil is also relevant for the cultural artifacts found in Amulsar however not much publicized. Some of the findings include ancient habitats, necropolises, graves. They are located on Amulsar mountain base some 10km south-east of Kechut village, as well as on Erato, Tigran, and Artavazd mountaintops of Amulsar. The project’s environmental and social impact assessment as well highlights the identification of 81 potential archaeological sites that will be impacted by the project.

Decision on relocating extinct plant species is one such adjustment of the local laws to this mining project instead of doing a responsible mining (if it is possible at all). Another twist was the regulation changes in 2015 on grading of pit ramps for haul roads: under the new regulation they have been increased to 10 percent from 7 percent in the past. The company highlights the environmental benefits of this move which will decrease the waste rock removed from the pit. The goal however has ultimately been significantly reducing operating costs of the mining, which would save the company some 100 million USD over the life of the mine and thus make it more attractive for investors. With this move the company hopes to increase the price for its shares in Toronto Stock Exchange, which have decreased from ≈3Canadian Dollars (CAD) (≈2.3USD) in 2011 to ≈0,34 CAD (≈0,27USD) in 2016.

Yet another example of fitting the laws under this project is the decision of the government to declare eminent domain over 0.975 hectare of agricultural land owned by private entities in Gndevaz for this project. In 2015 the company had already acquired 130 hectares of land located in the area of the heap leach facility. However, the Ministry of Justice has expressed its position (May 19, 2016 point 29) on this step declaring it contradicting to Article 60 (part 5) of Armenia’s Constitution. It states that eminent domain can be declared over projects in exclusive cases and only in case of prior equivalent compensation. This article envisages that eminent domain can be declared only for public or state needs and that these needs are conditioned by public’s prioritized interests. The Ministry clarifies that public need is displayed only in form of interests of the state and the communities. Moreover, article 4 (part 2) of Armenia’s Law on Alienation of Property for Public and State Needs provides cases when the property can be alienated for projects of national, communal or inter-communal importance. The Ministry stresses that this project has no substantiation of the project being of national, communal or inter-communal importance. This is a private project therefore alienation of the property on the grounds of public needs is a violation of the above-mentioned property right provided by article 60 of the Constitution.

One more example of creating favorable condition for the mining project was the decision of government in July 2013 (746-N) about Territorial planning of Sevan’s catchment basin. According to this decision Territorial planning of Sevan adopted in 2003 was changed and the coordinates of Vorotan-Sevan tunnel were amended changing the zone of catchment basin of the lake Sevan. This pushed the heap leach facility outside the zone affecting catchment basin of Sevan. On paper this removed the environmentally dangerous facility away from the impact zone of lake Sevan which is under special protection.

Speculations over uranium

Another issue in need of highlight is the presence of uranium in Amulsar. Its presence in Amulsar is denied both by Armenian government as well as by the company itself. However, an article published in a scientific journal Gornyi Zhurnal (Mining Journal) in 2007 about Armenian’s potential in radioactive resources, uranium in Amulsar was assessed at around 76 -100 tons.

The company refutes the scientific value of this article. Moreover, they demand the National Security Services to bring those who have disclosed previously secret materials of this Soviet expedition to responsibility. The project has therefore no assessment of how explosions will affect the diffusion of uranium into the environment. Meanwhile, Armenia’s Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources declares the absence of uranium in Amulsar referencing to the researches of Lydian International, not its own investigation.

Who is going to pay for the clean up?

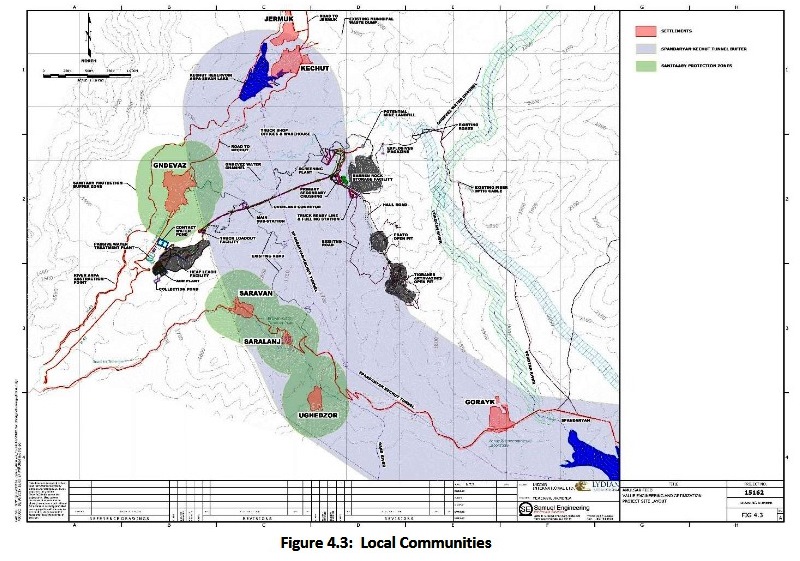

Some other concerns over the project include experts’ inquiry over how much fees will be paid for waste dumping, as well as how much money will be allocated for reclamation after the mining ends (i. e. funds for the process of restoring land that is mined to bring it to a natural or economically usable state). As they highlight, reclamation is a capital-intensive operation, since the company has to guarantee the state that the restoration process will be implemented. One such guarantee is capital deposit for reclamation in a separate account that will be used solely for the land reclamation after mining. Moreover, other specialists have calculated that if waste resulted from mining was taxed in Armenia it would be unprofitable to carry out this mining project. They mention that waste from this project is scaled as of the second degree of hazardousness. But even if it was scaled at degree four, which is the least hazardous, the company would have to pay the state around 350 million USD for its 100 million tons of waste. For second degree it would be some 5 billion USD.

Despite the absence of these measures and absence of any income from the project so far, Lydian has allocated a decent amount of money for funding social projects. One of the “investments” has been the allocation of 121.925.000AMD (around 254.000 USD) by Lydian’s subsidiary Geoteam CJSC to “Luys” foundation. This foundation provides scholarships to Armenian students studying abroad. Since it was founded by Armenia’s president Serzh Sargsyan and ex-prime-minister Tigran Sargsyan (currently the Chairman of the board of Eurasian Economic Commission), this and some other investments have raised concerns of corruption among environmentalists.

Company’s response to some of the problems

The company acknowledges some of the problems, such as “potential impacts of cyanide use to strategically important surface water features”, however according to them “the risks can be adequately managed from a technical view point.” The company acknowledges that “mining activities will result in permanent visual impacts and change of landscape through mountaintop removal and mine infrastructure construction. In addition, mine traffic, population influx and housing of the mine workforce will all impact local communities and the tourist potential of the area.” However, according to the company, jobs and opportunities that will be created for the locals will compensate the loss of incomes from tourism. There is no mention however about the loss of agriculture. The company also stressed that land acquisition procedures were all in line with international standards however the impact of the mine on biodiversity will be significant. The company mentions it has taken into account all concerns on this and other issues and will take measures to mitigate them.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development has backed the project with its statement “Notwithstanding E&S [environmental and social] complexities of the Project, the ESIA demonstrated the Project can be structured to meet the Bank’s requirements and the Company has committed to constructing and operating the mine in accordance with international best practice”.

Lydian International enjoys the support of some other figures too, such as former and current ambassadors to Armenia. While Lydian’s two main projects are gold at Amulsar in Armenia and zinc, lead, silver and gold at Drazhnje in Kosovo, US Ambassador to Armenia Richard Mills, during his visit to Amulsar with the Prime Minister of Armenia in August 2015, mentioned that “Lydian International is known for utilizing responsible mining practices that adhere to international environmental standards”. Lydian International may pat itself on the back for getting the firm support of the current, as well previous US and UK ambassadors to Armenia for this project despite its relatively short mining experience.

Complaints processed by Compliance Advisor Ombudsman

Meanwhile, based on complaints of local NGOs and residents in Gndevaz and Jermuk, Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO), which is the independent office for accountability of the International Finance Corporation (IFC), is reviewing the effects of IFC supported project. The complainants expressed their concerns over lack of adequate stakeholder consultations around the project; criticism of national EIA process conducted by the company; alleged violations of IFC’s Performance Standards, national regulations; inadequate project information about land acquisition and resettlement plans; environmental contamination from the project’s cyanide leaching system; dust pollution affecting environment and communities, their livelihoods; concerns for cultural heritage; employee and community health issues; insufficient community engagement. The complaint is being reviewed at the moment. Based on its initial review of the project, the CAO raised its concerns regarding environmental and social outcomes of the project and implementation of the IFC’s policies, procedures, standards. However, as there were additional complaints and issues raised in the process of review, the Office is at the moment continuing its examination and the disclosure of the decision is expected in summer 2016. The hope is that IFC’s 7.9 percent shares and 13 million USD investments will not interfere with just decision making.

Implementation of the project will bear significant risks, some of which include violations of the following international norms:

- the right to take part in the conduct of public affairs as the residents complain of inadequate project information and lack of adequate stakeholder consultations; (ICCPR, Article 25) (Aarhus Convention)

- the right of residents in nearby villages, communities and towns to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, including through improvement of all aspects of environmental and industrial hygiene; (Article 12, ICESCR)

- right to an adequate standard of living for the residents and their families, including adequate food, housing and continuous improvement of living conditions; (ICESCR, Article 11)

- and connected to this is the right to water; (ICESCR, Article 11, 12)

- the locals’ right to work and gain their living by work, including those residing in Jermuk, whose jobs are connected with tourism and spa resort, as well as those who benefit from agriculture, however whose lands are not included in environmental and social impact assessment; (ICESCR, Article 6)

- Cultural rights (ICESCR, Article 15), which include state’s obligation to take measures for conservation, development and diffusion of culture.

Moreover, taking into account the numerous cases of abuse of political resources and thus decision making which have adjusted Armenian laws to the project, instead of the project conforming to national and international laws, IFC, EBRD and other shareholders seriously risk being accomplice in corrupt processes in Armenia hampering its democratic processes and sustainable development.

Pan-Armenian Environmental Front (PAEF) civil initiative

P.S. Here you can get acquainted with some of the opinions, analysis, articles and videos by experts on gold mining in Amulsar.